Roosevelt, Taft, Wilson

- TR: My view was that every executive officer, and above all every executive officer in high position, was a steward of the people bound actively and affirmatively to do all he could for the people, and not to content himself with the negative merit of keeping his talents undamaged in a napkin. I declined to adopt the view that what was imperatively necessary for the Nation could not be done by the President unless he could find some specific authorization to do it. My belief was that it was not only his right but his duty to do anything that the needs of the Nation demanded unless such action was forbidden by the Constitution or by the law

- Taft: The true view of the Executive functions is, as I conceive it, that the President can exercise no power which cannot be fairly and reasonably traced to some specific grant of power or justly implied and included within such express grant as proper and necessary to its exercise. Such specific grant must be either in the Federal Constitution or in an act of Congress passed in pursuance thereof.

- Wilson: The President is at liberty, both in law and conscience, to be as big a man as he can. His capacity will set the limit; and if Congress be overborne by him, it will be no fault of the makers of the Constitution, — it will be from no lack of constitutional powers on its part, but only because the President has the nation behind him, and Congress has not. He has no means of compelling Congress except through public opinion.

White House spin and the Dreyer memo (Once again -- do not confuse with CMC's David Dreier!)

----------

----------

Here is a concise guide to federal statutes.

After Congress passes law, the bureaucracy drafts rules:

Madison in Federalist 62:

The internal effects of a mutable policy are still more calamitous. It poisons the blessing of liberty itself. It will be of little avail to the people, that the laws are made by men of their own choice, if the laws be so voluminous that they cannot be read, or so incoherent that they cannot be understood; if they be repealed or revised before they are promulgated, or undergo such incessant changes that no man, who knows what the law is to-day, can guess what it will be to-morrow. Law is defined to be a rule of action; but how can that be a rule, which is little known, and less fixed?

Another effect of public instability is the unreasonable advantage it gives to the sagacious, the enterprising, and the moneyed few over the industrious and uniformed mass of the people. Every new regulation concerning commerce or revenue, or in any way affecting the value of the different species of property, presents a new harvest to those who watch the change, and can trace its consequences; a harvest, reared not by themselves, but by the toils and cares of the great body of their fellow-citizens. This is a state of things in which it may be said with some truth that laws are made for the few, not for the many.

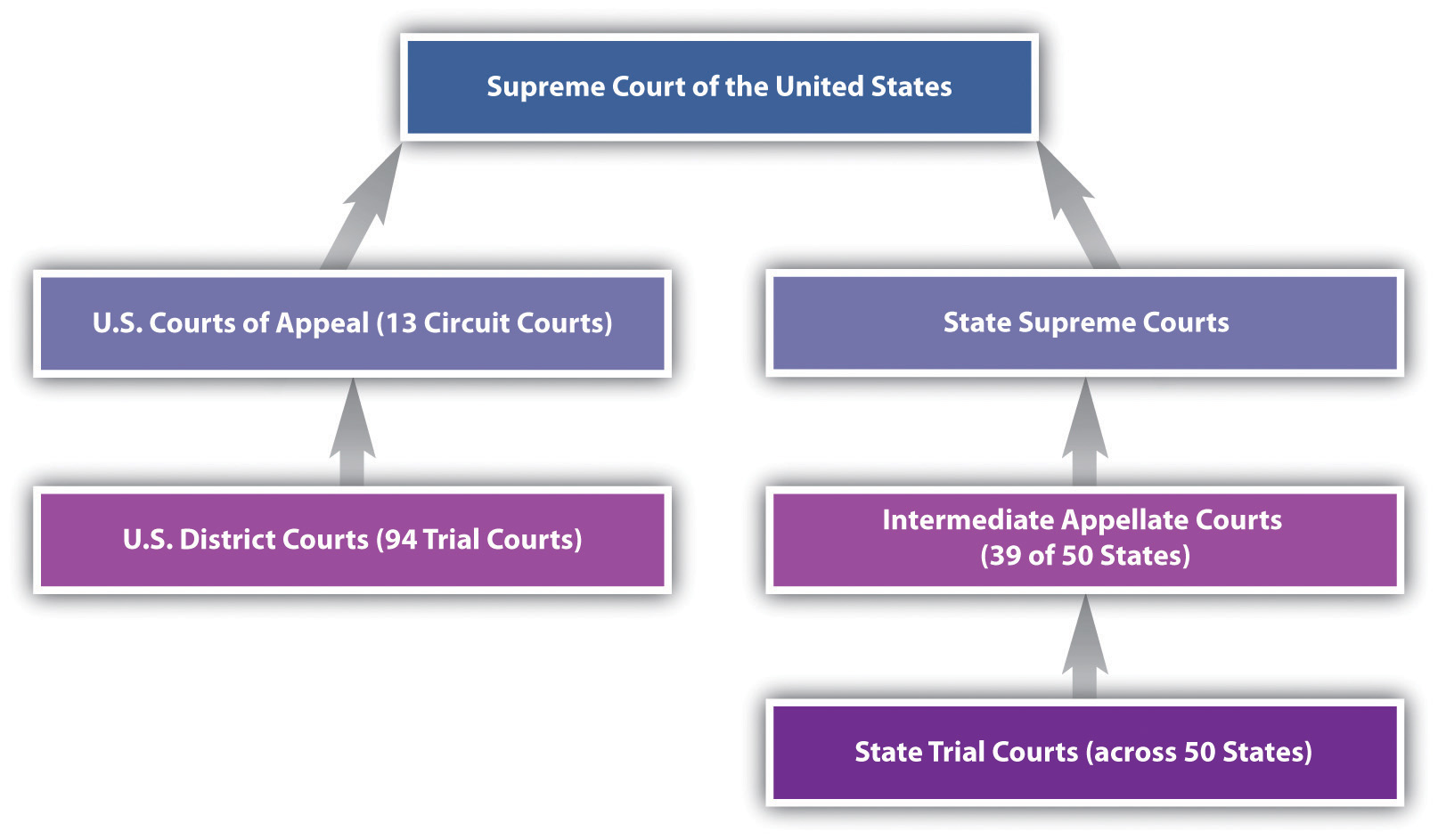

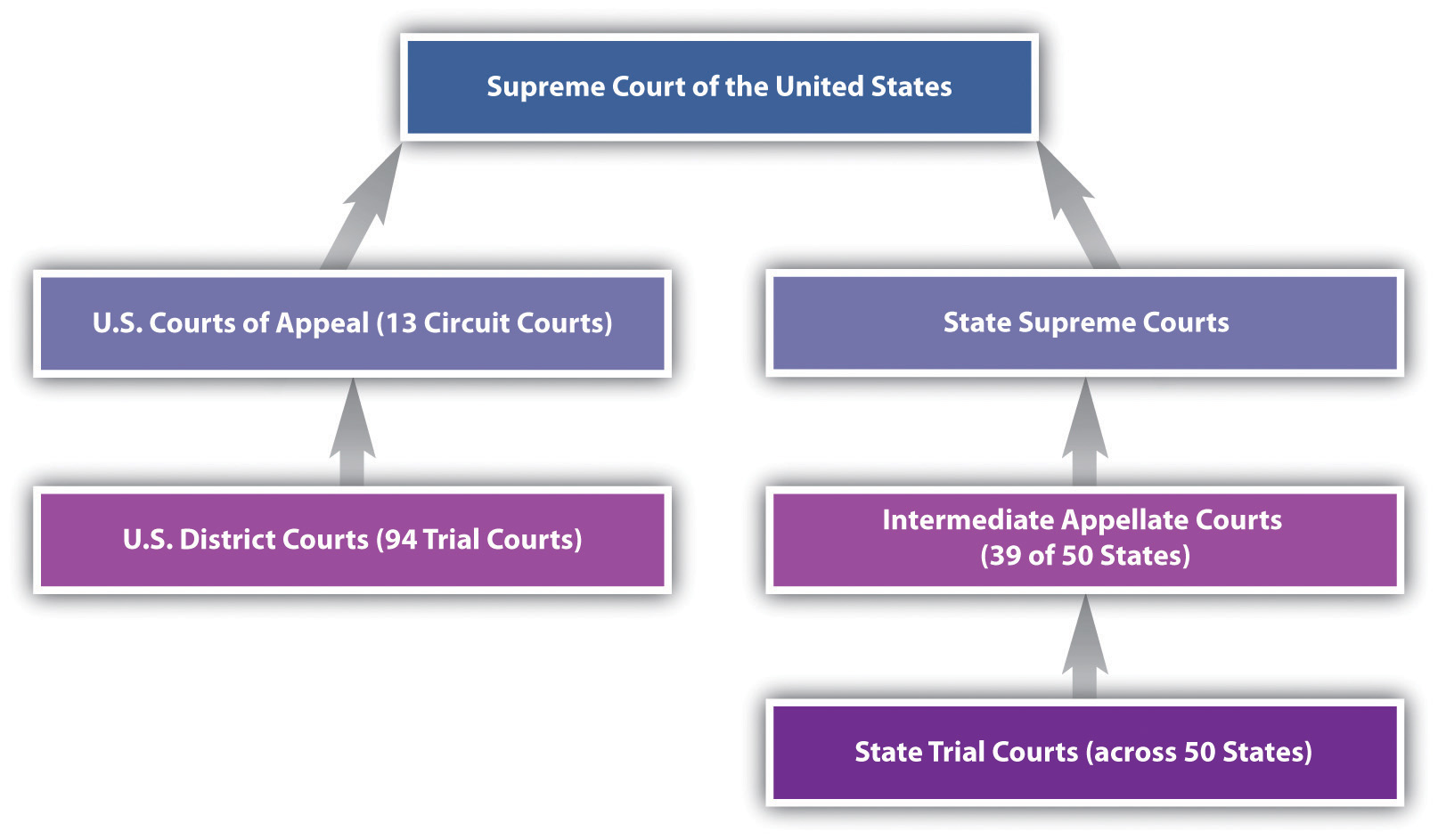

Appellate Courts

- Federalist 78

- Marbury v. Madison

- The Structure

- Guide to Supreme Court decisions

- Tocqueville (p. 267): "Our written laws are often hard to understand, but everyone can read them, whereas nothing could be more obscure and out of reach of the common man than a law founded on precedent.”

- Tocqueville (p. 270): “There is hardly a political question in the United States which does not sooner or later turn into a judicial one”

- One example of many: the travel ban.

The Dangers of the Law

- The "joy" of jury duty

- My jury experience

- Tocqueville (p. 275):

Juries invest each citizen with a sort of magisterial office; they make all men feel that they have duties toward society and that they take a share in its government. By making men pay attention to things other than their own affairs, they combat that individual selfishness which is like rust in society.

Juries are wonderfully effective in shaping a nation’s judgment and increasing its natural lights. That, in my view, is its greatest advantage. It should be regarded as free school which is always open and in which each juror learns his rights, comes into daily contact with the best-educated and most-enlightened members of the upper classes, and is given practical lessons in the law, lessons which the advocate’s efforts, the judge’s advice, and also the very passions of the litigants bring within his mental grasp. I think that the main reason for the practical intelligence and the political good sense of the Americans is their long experience with juries in civil cases.

No comments:

Post a Comment